By Rebecca Bengal | Originally Appeared in Vogue

It was the summer of 1983. Mark Steinmetz, then 21, dropped out of Yale art school and headed, on a bit of a whim, to California. He’d grown up in the Northeast. He thought he might like to work in movies. And he wanted to meet a hero of his, the photographer Garry Winogrand, who for years lived in Los Angeles, shooting his way through some 8,000 rolls of film.

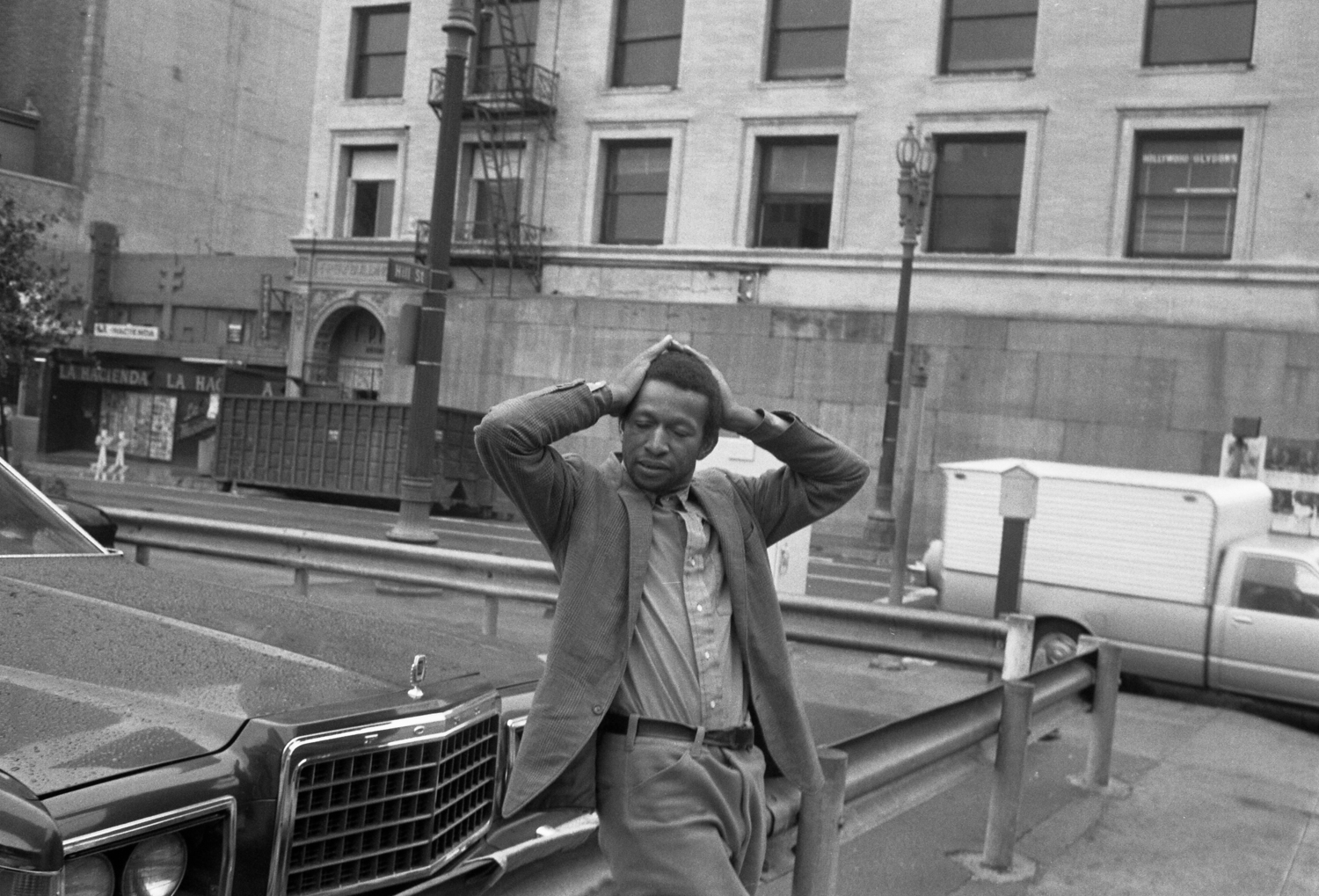

In L.A., the golden dream fizzled a little. Roaches ran over the futon on the floor in Steinmetz’s studio apartment, in which he’d also managed to fit a darkroom. Someone told him that Winogrand had just left town. But that person turned out to be wrong, and Steinmetz’s instincts were proved weirdly, serendipitously correct: That summer he started running into Winogrand everywhere, in the most far-flung, unlikely parts of the city. “Garry never saw anything of mine,” Steinmetz said in a recent phone call. “He just knew me as a guy with a camera. But I guess I spoke about photography in a way that was acceptable to him. And he was a guy who really just wanted to hang out and do his work.” Driving around Los Angeles in Steinmetz’s champagne-color Fiat, they’d each make photographs. The work turned out to be some of Winogrand’s last (he was diagnosed with cancer just months after Steinmetz first struck up a conversation with him; he died on March 19, 1984, leaving behind thousands of undeveloped photographs); but they were among some of Steinmetz’s earliest pictures, and are published for the first time in his new book, Angel City West, (Nazraeli Press).

Winogrand was a teacher only in the loosest, most accidental sense, breezily steering Steinmetz away from, in his words, the bullshitters, nonsense, and seductions of the world. “His cheerful, practical manner and advice probably helped me shave off years of worrying how to be,” Steinmetz writes in the book’s essay. Though Winogrand may never have seen these pictures, his influence hovers all around them—the second angel of Angel City West. The first, of course, is Los Angeles itself.

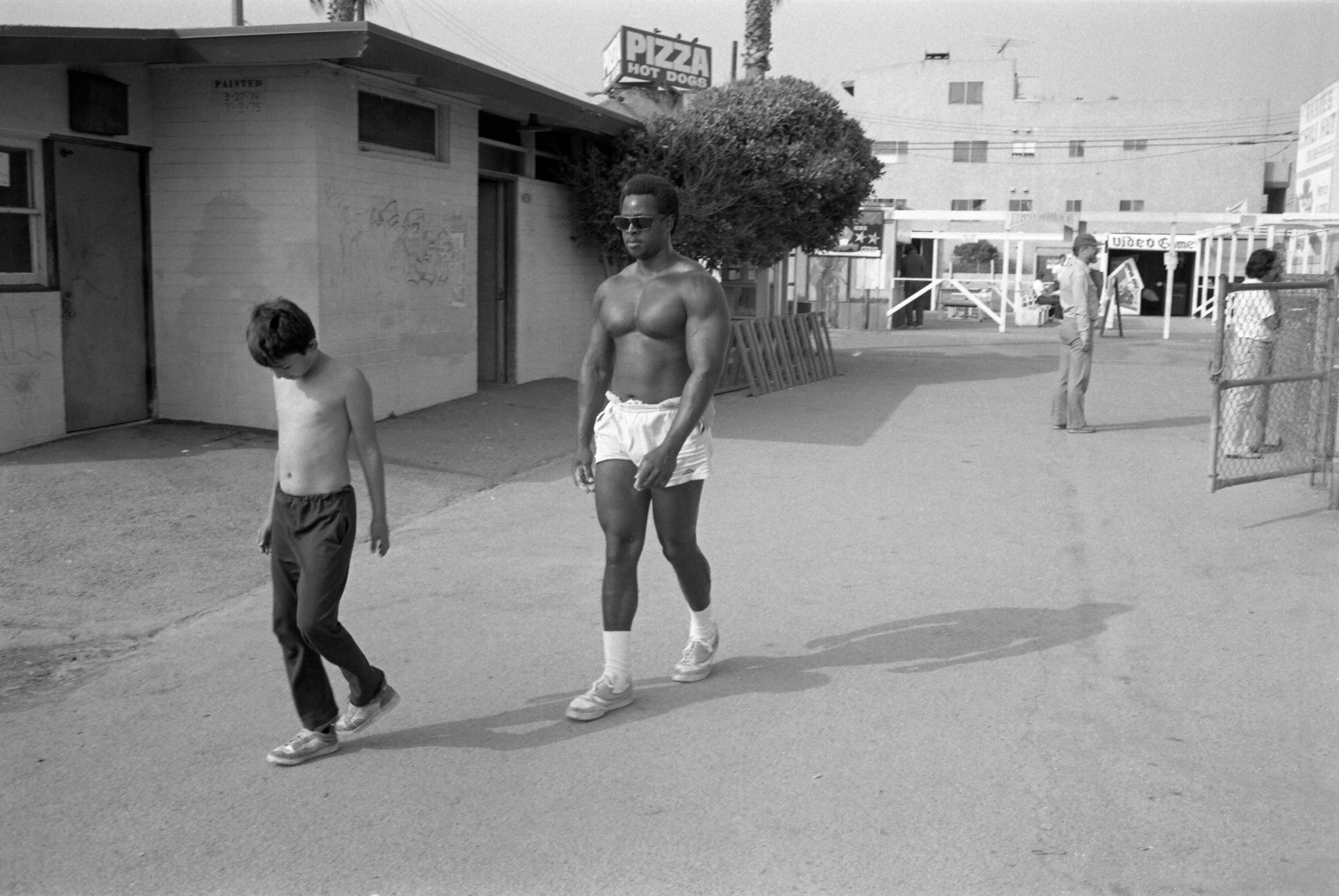

“There’s a certain atmosphere, a certain mood, a certain exoticism to different places, and I want to squeeze that into the frame, not so explicitly, but I just want to let that rain over the picture,” Steinmetz says. “I come from a cinema background—film noir—it’s so important to get that kind of atmosphere into the picture. Certain places just get you pumped up to describe that.”

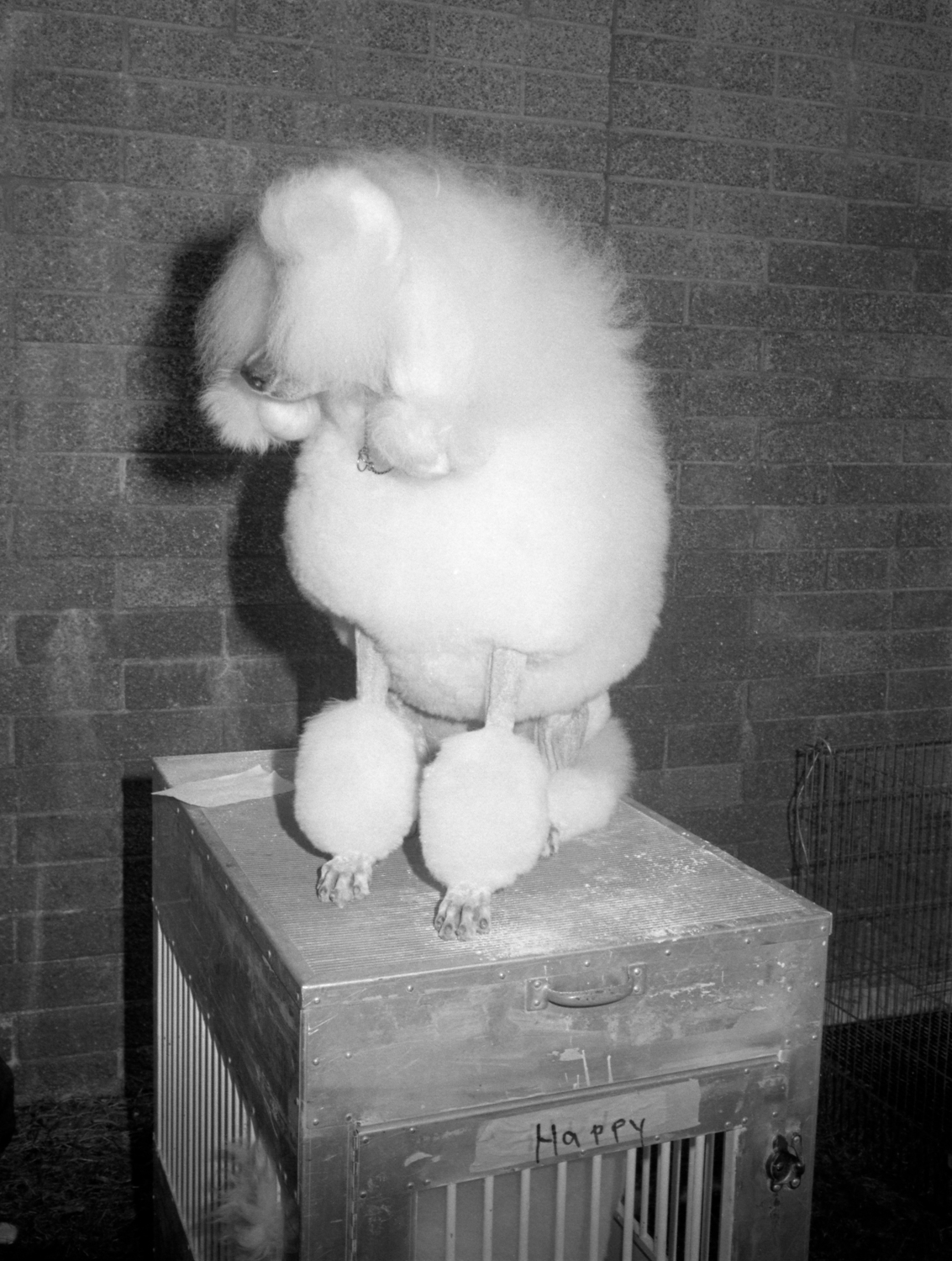

A roller skater, a family gathered around a boom box, a woman waiting for the traffic light to change—the situations are fairly unremarkable. But the pictures record light-changing moments, catching subtle uncommon flashes amid the everyday: delightfully odd discoveries so casually delivered you feel as if you’ve stumbled upon them yourself. Steinmetz’s subsequent, widely exhibited bodies of work wander along city streets, through parking lots at night, backyards, and baseball fields in Italy, Paris, and around the American South, especially in and around Athens, Georgia, where he has lived and worked for many years. Un-orchestrated and artful, his photographs rely on a kind of magic convergence of chance and observation and craft. “Mark Steinmetz works in a venerable tradition of photographic prowling that bets everything on the ordinary,” wrote Museum of Modern Art curator Peter Galassi of an earlier book, South East.

“You go with the flow, you keep your eyes open, and you follow your intuitions,” says Steinmetz. The way he shoots in L.A., Miami, Memphis, or anywhere these days is much the same now as it was in 1983, cruising the freeways with Winogrand or walking the streets solo. It was a purer era in photography back then, though, he says, before a feeling for fictional tableau over straight photography took hold, before “interesting” pictures were valued over beautiful images, before color dominated black and white.

As we speak, Steinmetz spools back to the language of cinema. “There are emotional notes that black and white can deliver that color cannot,” he says. “It’s a different medium. It’s like silent film. You know, Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin delivered some moments where they killed you. They just absolutely killed you. It’s not going to happen like that again, with sound.”