Mark Steinmetz, Artist

Jack Deese (JD): You’re currently working on a project that is part of the “Picturing the South” commission for the High Museum, and you’re photographing in and around the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. How long have you been working on the project, and when did it first present itself to you as an area of interest?

Mark Steinmetz (MS): I moved to the Athens, Georgia, and Atlanta area in 1994, and I have photos from back then of families watching planes taking off while they picnic on their cars. I’ve always thought that airports were good places to photograph and have taken photos at airports every time I travel. I was asked a few years ago what project I would work on if I were offered a “Picturing the South” commission, and I said I would like to photograph the Atlanta airport. The commission wasn’t officially offered to me until last year, but I started to concentrate more on photographing around the airport two or three years ago.

JD: I imagine gaining access to a huge bureaucracy like that must present a number of challenges. How difficult has it been, and what are some of the challenges you’ve faced?

MS: The High Museum wrote a letter on my behalf to explain that I am working on a project for them, but so far I haven’t shown it to anyone and nobody has asked me what I am doing. I travel a lot and am often photographing while I have a suitcase alongside me. Sometimes I am picking up or dropping off a friend, and I linger to photograph. Also, a large part of the project is photographing on the outskirts of the airport—the surrounding hotels and parking lots, the neighboring towns. I am pretty discreet and have a quiet camera, and I often talk to the people I am photographing if I think that is the best way to make the picture. I don’t stay in one spot for too long. It’s possible I would need to ask the airport for the kind of access that would help me make some photos, such as getting out onto the tarmac or photographing from the observation tower or a rooftop, but so far I simply have had the same access that anyone has.

JD: You often show your work in book format. How are decisions on editing and sequencing different for you with an exhibition versus a book?

MS: My books are fairly traditional in that the images are pretty much the same size within each book, and they appear in a set order with particular emphasis given to how the images work together as pairs across a spread. On the museum wall, I will have photographs of different sizes. Some will be very large and given lots of space on the wall, and some will be much smaller and perhaps arranged in grids of four. In the larger prints, you can experience the images more with your body than your intellect and pick up on details that are not readily noticed when the image appears small on a page. In larger prints put up on the wall, it’s easier to see the differences between the film formats used. On the page, it doesn’t matter so much whether a photo was printed from a 35mm negative or from a 6 x 9 cm negative. We are still far from making exhibition decisions for the show at the High.

JD: Are you performing regular edits as you progress in a project, or do you prefer to make all the photographs before you begin to access them?

MS: For this commission I have been scanning the negatives to check on the results. There are some night images and photographs made with the telephoto lens (which is new for me), so I want to make sure those are working out from a technical perspective. I want to get a good look at the pictures soon after their making so I can be sure I am not kidding myself about their quality. I pool together images so I can come to understand how I might be repeating myself and to determine whether there are still some kinds of subjects that are missing from the body of work.

JD: If something is missing, will you go out to photograph looking for a certain type of photo to fill in that void? And is that looking for something particular only helpful for you after a body of work has begun to naturally shape itself?

MS: I try to stay open to the range of people and scenes and narrative actions that can be found in and around the airport, but over time I start to come up with a few subjects in particular that I think would be good to keep in mind. For the airport project, for instance, I really hope to have at least one strong photograph of a pilot wearing one of those pilot’s caps. This could be on the plane, or somewhere around the airport, or on the sidewalk outside the airport as the pilot waits for a ride home. Mostly photography is about responding and discovering; too much prescription can lead to boring work, but some guidelines can be helpful and bring about a sense of fullness to the work.

JD: I feel your photographs are often hard to place in a particular time period. Do you feel that’s true, and if so, is it a conscious effort on your end to achieve that?

MS: I largely avoid topical, newsworthy themes but I also have little tolerance for photographs that look like they might have been taken in an earlier (usually simpler) period of time. In general, I photograph scenes that might be specific in terms of weather, season, or time of day but which don’t refer too closely to any particular day of the calendar or any historical event. I view my work as a record of our contemporary civilization—framed loosely as anytime in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Earlier on I photographed people at pay phones and phone booths; nowadays everyone is glued to their cell phones and I photograph that. The cars on the streets today look different than the ones from thirty years ago—so time marches on, and while I don’t want to cling to the look of a previous decade, I am also not strongly inclined to examine the latest societal shift. My Little League Baseball photos (“The Players”) could have been made at any time since the dawn of the chain-link fence, and my Paris photos (“Paris in My Time”) are set against the unchanging classical backdrop of that city, so the particular period for those bodies of work might be harder to place.

JD: Given recent events such as various protests, the airport seems like it could be rife with topical subject matter. Has this affected how you’ve approached photographing over the past few months?

MS: Not really. As far as I could tell, the protests at the Atlanta airport were fairly mild. I have images of headlines from newspapers and the ubiquitous television screens (CNN is headquartered in Atlanta) about the election or the Zika outbreak, and some of those headlines are absurd and funny or troubling, but I don’t know if I’ll finally use them in a show or book. There have also been major breakdowns with computers that have left crowds of stranded passengers, but for the most part, my photos could have been made on any ordinary day.

JD: I know you primarily shoot film; is that still the case with the airport work? Are you still producing your own silver gelatin prints?

MS: I’ve shot a tiny bit with a digital Leica at the airport to see if that would help with the underlit corridors of the airport, but I prefer film and making my own silver prints. I feel if I’ve made a digital print, I really haven’t made much of anything. A few negatives have some air bubble damage from development and are improved by digital correction, and maybe those I would print digitally. It’s only possible for me to make 20 x 24″ silver gelatin prints in my darkroom; these are small by today’s standards. It’s much easier and cheaper to make a large print digitally than in the darkroom.

JD: Is printing larger than 20 x 24″ something that interests you? I feel your images have an intimacy to them that might be lost in a large print.

MS: I’m a maker of photography books and I want my photographs to succeed on the page, so my pictures need to be able to work small. Large prints, up until recently, have always seemed as something of a bourgeois extravagance to me. But they can be wonderful. I currently have a show up in New York City, and for the first time, many of the prints are very large (30 x 40″ and even larger). The large ones were made by a friend in Brooklyn (Sergio Purtell), based on match prints that I had I sent him. In a book, photos are frozen in sequence and often yoked together in pairs. In a show, the photos can be placed in new arrangements. Big prints can offer up new details that the small image on the page cannot, so the images can be experienced freshly; one’s body participates more in how the work is felt—the experience is more visceral.

JD: What’s your level of excitement with photography at the moment, both your own and the medium as a whole?

MS: The medium of photography is this huge mammoth beast. My corner of the medium is really rather small in terms of audience; what I do is overshadowed by other intentions and other uses of photography. For myself, I’m still super excited and raring to go for my next photo, my next project. In some ways Evans and Frank have succeeded in creating photography’s version of “The Great American Novel.” I kind of wish more photographers had this large ambition, this grand sense of purpose. Many photographers today are making work that is fresh (and surprising), new and modern, and highly competent, and they are making a wonderful contribution to the medium. But sometimes I feel like asking for a little more madness. Is there anybody out there now as crazy and driven as someone like Winogrand? Atget seemed to be photographing for The Gods. Who today is working for The Gods?

JD: Do you feel a lot of photographers are following formulas? Not only for image creation, but the ways in which they’re seen and spoken about? What else do you think is aiding in this lack of madness?

MS: I think in the old days there were fewer teaching jobs, less money overall, and a much smaller art market. Living in a city was easier then. The rents were lower, health care costs and insurance premiums were lower, nobody was that rich, and life wasn’t that fancy. You just bought a cup of coffee; now it’s some kind of deluxe cappuccino. Today you have to have a cell phone and an Internet connection, and many young artists who have gone to art school need to pay off their student loans. All this costs money, and so photographers must work and work to meet their expenses, particularly those that live in large cities. This keeps everyone in a state of low-grade servitude. The generation of photographers that preceded us (such as Robert Adams and Winogrand) lived fairly simply in comparison to today’s generation. I think they were able to shape lives for themselves that didn’t have too many distractions. They could work with diligence and sincerity, and whatever came from that could blossom.

I’m uncomfortable making generalizations about what photographers these days are up to. There are so many approaches. A common stance today is to combine styles and picture-making strategies: a photographer in the same body of work will mix up abstract, blurry photos with sharp, descriptive ones. The trend is to do a little of this, a little of that: now here’s something done on commercial assignment and now something from an archive, etc. Photos of varying sizes are arranged on the wall in a nonlinear way. I think it’s healthy to push against older, more traditional forms, but hopefully this is bringing about some kind of freshness, some sort of improvement. Stories and meanings are often getting lost in the dazzle, and books and exhibits suffer from design impulses that are too ambitious.

I might be having a problem with the directions today’s curators are taking, but I don’t really want to get into this subject. Perhaps they don’t have enough experience actually making photographs.

JD: You received your M.F.A. from Yale and spent time learning under Garry Winogrand. You’ve also taught at various times. What do you feel is the most effective way to learn the medium?

MS: I hung out with Garry and drove him around L.A. on a few occasions—there was nothing remotely resembling formal instruction when I was with him, but you can pick up a lot from someone just through osmosis. The M.F.A. is a wonderful luxury, and if someday you want to teach, a necessity. It allows you to take two years to focus on your work and to share your process in a group environment. In some cases, the students get turned around and around a few times too many and then leave their programs overthinking their chosen photographic predicaments. I’ve taught over a dozen intensive workshops and have seen a lot of benefit and growth take place in that format. Reading great books and looking at great works of art can help steer photographers to make work that is worth making.

JD: What happens to your photos that haven’t made the cut for one reason or another over the years? Do you revisit them, and if so, how does the distance make you think of them?

MS: Once in a while there’s a serendipitous (an out-of-the-blue) request for images, perhaps for a particular subject, and I will dive in and go over contact sheets if they exist. Nowadays, I have an assistant who scans old negative sheets, and so more and more work is brought to light. The distance of years helps me to view the contacts with detachment, and since the world has changed, some of the things I photographed way back when might take on greater interest now—such as hairstyles or car models or clothing.

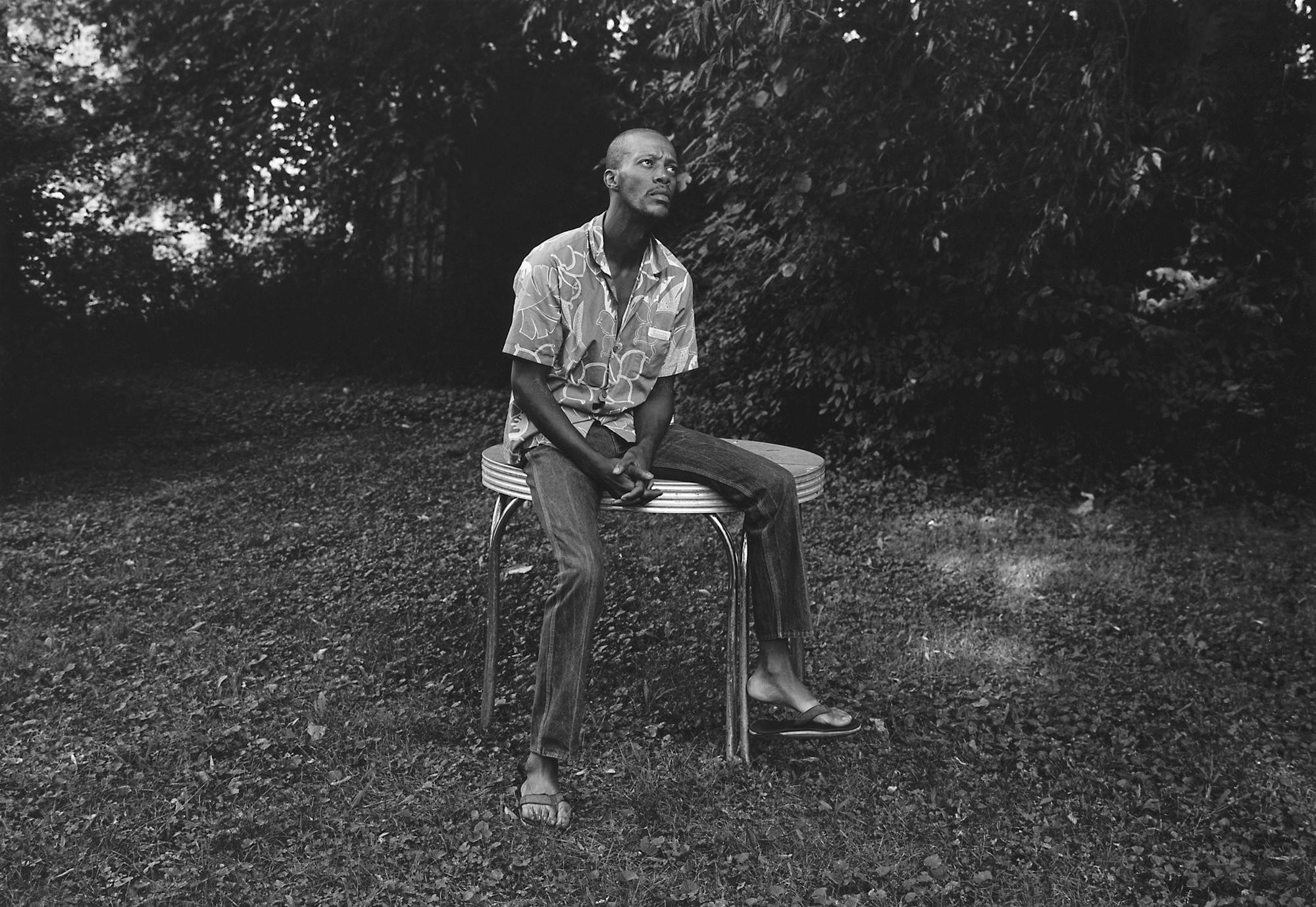

When I was younger, I would photograph all the time, but I also had to make ends meet. As far as I could tell, nobody was terribly interested in what I was doing, and before there was an Internet, there was no easy way to share one’s work. Over the years, the work has piled up. I have four years of work in Chicago that I’ve hardly looked at, and this morning I went to a flea market in Athens, Georgia, where I’ve photographed for over twenty years—that work hasn’t been examined very much either.

JD: Outside of the airport work, what other projects are you currently working on?

MS: I’ve been traveling a lot and have been photographing on the streets of major cities: so far Paris, Berlin, Bangkok, Hong Kong, and hopefully the list will grow. Otherwise, I’ve been photographing close to home and in my home and backyard. I now have a little baby daughter, and she’s my greatest project.

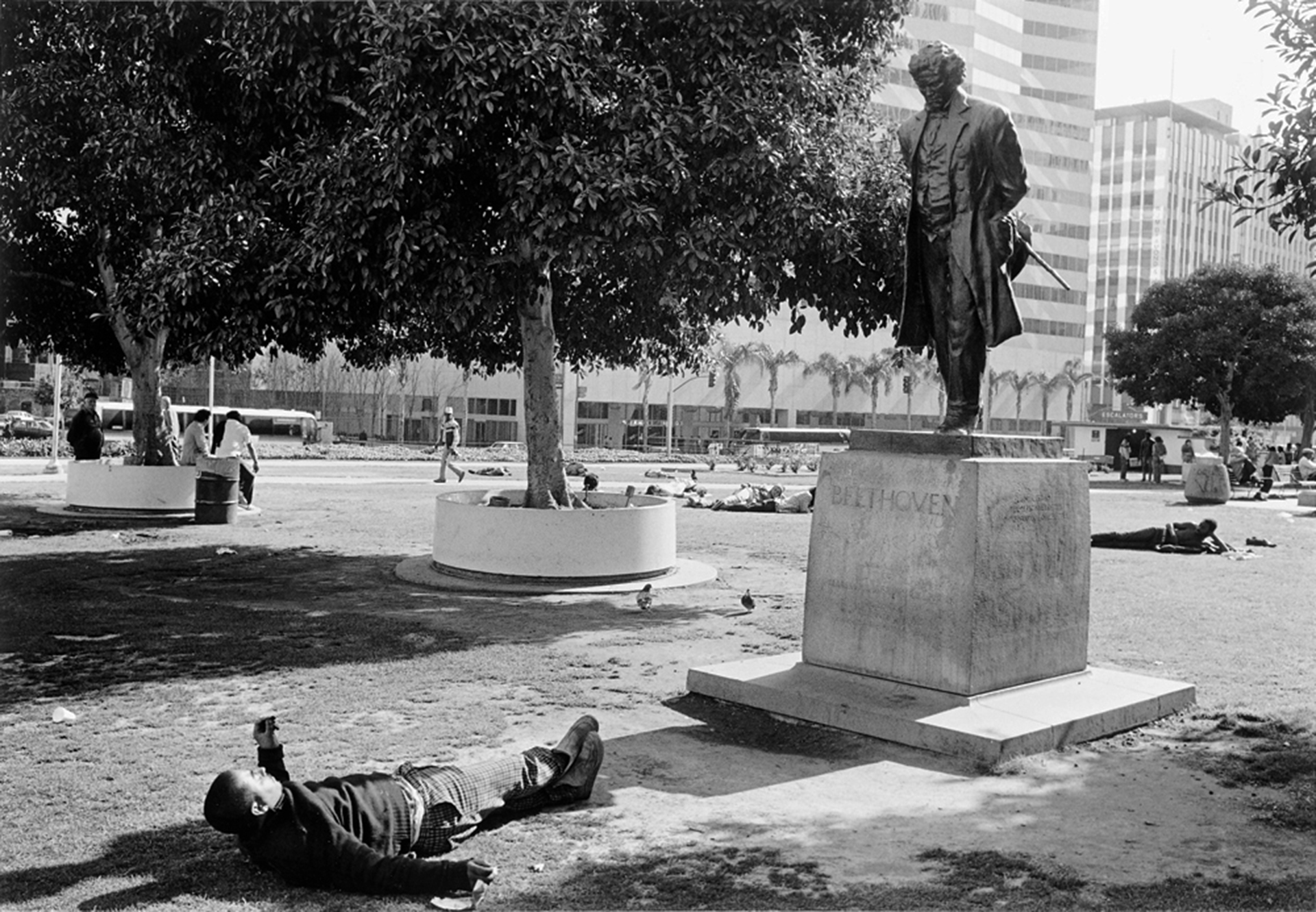

I’m having two large shows in Munich this fall which takes a lot of time to print and organize, and I’ve still been working on books, bringing out older work (there will finally be three volumes of “Angel City West,” which are photos from Los Angeles made back in the early ’80s, and the “Summer Camp” book will come out—in some ways it pairs with “The Players,” which is about Little League Baseball). I’m asked from time to time to do a fashion shoot or a creative project such as making photographs in Atlanta today that refer to a particular Walker Evans photograph from 1936.

JD: What are you reading, watching, or listening to right now?

MS: I wish I had more time for all of that! I’ve been purchasing photo books though many are set aside and stay in their wrappers until there’s a moment to look at them. I’ve been paying attention to these (for me) sad and disturbing days in America’s politics and am trying to keep my mind in a healthy place: fresh and clear.

JD: What are some of those recent photo books you’ve purchased?

MS: I have a book of Henry Wessel’s, recently published by Steidl, which I like a lot—the section on traffic is delightful. I bought a reissue of “Ravens” by Masahisa Fukase and Aperture’s book on Stephen Shore called “Selected Works”—both of those are still in their wrappers, as is a Thomas Struth book on nature and politics. Tom Roma sent me his “Plato’s Dogs” and Robert Adams sent me his “Art Can Help.” I bought Lee Friedlander’s recent street photography book published by Yale and MoMA’s book on the old New Documents show (which I have not yet opened). I’ve preordered “Election Eve” by Eggleston as well as the book “Cezanne’s Objects” by Joel Meyerowitz, as I have a small collection of photo books relating to Cezanne (also bought Sally Mann’s similar book on Cy Twombly’s studio). Also: Peter van Agtmael, “Buzzing at the Sill”; Jitka Hanzlova, “Horse”; Martin Parr, “Conventional Photography”; and Dorothee Deiss, “Visible Invisible.” There are several more scattered about. Hopefully I’ll catch up with my work and have time one day to go through all the books and put them into some order in my bookcases.

Interview conducted by Jack Deese through email over the course of a few months (June-September).

See more of Mark’s work on his website.